Abstract

Introduction: AHCT remains a standard of care in multiple myeloma (MM) patients especially in the frontline setting. Studies exploring the long-term effect of the time to neutrophil engraftment on survival post-AHCT in MM patients remains scarce. In addition, a better understanding of the implication of certain demographic, clinical and cytogenetic factors on the engraftment process is needed. Here, we studied patient and disease specific factors impacting the engraftment processes as well as its effect on survival in MM patients.

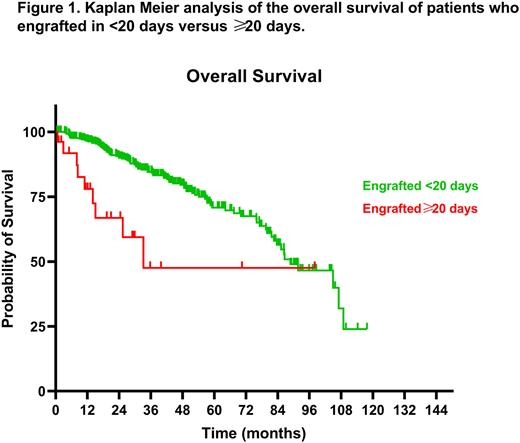

Methods: The electronic medical records of all MM patients who underwent AHCT between 2011 and through 2020 at Cleveland clinic were reviewed. Patient specific characteristics that were analyzed included age at diagnosis, age at AHCT, sex, smoking history (current, ex- or never), time to transplant (<12 vs ≥12 months), albumin level at diagnosis (<3.5 g/dL or ≥3.5 g/dL), cytogenetic risk abnormalities (High risk: HR or Standard risk: SR), ECOG performance status (0, 1, 2, 3 or 4), International scoring system stage (I, II or III), pre-AHCT number of treatments (1 or ≥2), disease status pre-AHCT (PR: partial response; VGPR: very good partial response; CR: complete response), CD34+ dose used, and days to engraftment. Neutrophil engraftment was defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 500/mm3 or more for three consecutive days. A cut-off 20 days was chosen and tested for long-term outcomes using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, whereas chi-square and t-tests were followed by multivariate analysis to confirm factors that independently influence engraftment.

Results: A total of 431 patients were included in our study, of whom cytogenetics and ISS were available in 346 and 352, respectively. Our cohort had a median age at AHCT of 61.3 years (range 33.1-77.8 years), male preponderance of 56.6%, median time to neutrophil engraftment of 12 days (range 9-61 days), and median follow up of 32.5 months (range 0.6-117.8 months). Applying Kaplan Meier survival analysis when dividing patients into early engraftment (<20 days, n=405) and delayed engraftment (≥20 days, n=26) groups yielded a remarkably significant difference in mOS post-AHCT (88.8 vs 33.2 months, P<0.0001) (Fig 1). This was consistent with 1-year and 3-year mortality rates of 38.46% (vs 14.22%, P=0.0031) and 88.46% (vs 52.45%, P=0.0003) for the ≥20 as opposed to the <20 days to engraftment groups, respectively. Subgroup analysis further emphasized the lower survival in the ≥20 days vs <20 days in the setting of non-relapse (medians unreached, P=0.0096) as well as relapsed disease (mOS 25.4 vs 77.2 months, P<0.0001), respectively. A lower, albeit non-significant, median progression free survival (mPFS) was also seen in the ≥20 days engraftment group (36.8 vs 46.6 months, P=0.5).

Looking into factors that may affect time to engraftment, delayed engraftment (≥20 days) was associated with female sex (73 vs 41%, P<0.0001), ISS stage III (31.6 vs 22% P<0.0001), HR cytogenetics (44.4 vs 29.5%, P<0.0001), and IgA MM (52.4 vs 22.2%, P<0.0001) compared to early engraftment (<20 days). No difference was seen with regards to age at AHCT (median 61.6 vs 60.7 years, P=0.5), history of smoking (23 vs 38.3%, P=0.3), ECOG performance status pre-AHCT (P=0.2), albumin levels at diagnosis (<3.5 g/dL in 25 vs 26.6%, P=0.9), disease status pre-AHCT (PR 42.3 vs 40.2%, VGPR 34.6 vs 33.8%, CR 23.1 vs 26% P=0.9), mobilization regimen (G-CSF + Plerixafor in 92.3 vs 90.6%, P=0.9), time to transplant of ≥ 12 months (34.6 vs 29%, P=0.5), recent immunomodulatory drugs use (69.2 vs 66.9%, P=0.9), pre-AHCT lines of treatment (≥ 2 in 42.3 vs 35.8%, P=0.6). Delayed engraftment was associated with a lower, though not statistically significant, median CD34+ dose (4.7 vs 5.2 x106, P=0.08). Multivariate analysis further confirmed the association of HR cytogenetics with delayed engraftment (HR 5.2, 1.2-27.8 95% CI).

Conclusion: Early engraftment, defined as in less than 20 days, confers better overall survival rates post-AHCT, including among both relapsed and non-relapsed patients. Time to engraftment is mainly associated with patients' cytogenetic risk categorization.

Disclosures

Winter:Janssen: Consultancy, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Seagen, Inc: Consultancy, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; OncLive: Honoraria. Sauter:Precision Biosciences: Other: PI; BMS: Other: PI; Gamida Cell: Consultancy; Kite Pharma Inc.: Consultancy; Genzyme/Sanofi: Other: PI; CSL Behring: Consultancy; Ono Pharmaceuticals: Consultancy; Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc.: Consultancy. Hill:Kite, a Gilead Company: Consultancy, Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Other: Travel Support, Research Funding; Novartis: Consultancy, Honoraria, Research Funding; BMS: Consultancy, Honoraria, Research Funding. Valent:Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease: Research Funding. Jagadeesh:Trillium Pharmaceuticals: Research Funding; Seagen: Research Funding; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.: Research Funding; MEI Pharma: Research Funding; LOXO Pharmaceuticals: Research Funding; Debio pharma: Research Funding; Daiichi Sankyo: Consultancy, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; ATARA Biotherapeutics: Research Funding; AstraZeneca: Research Funding; Affimed: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees. Hamilton:Kadmon: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Equilium: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Incyte: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Nkarta: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Syndax: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal